All pics courtesy of faithful reader yellojkt, who came to my party!

Some of my earliest TV memories were of watching Jeopardy with my mother. The current incarnation of show is 24 this year, and I’m 34, and I actually remember the media blitz when they launched the new, Alex Trebek-hosted version. This is because at the age of 10 I was susceptible to advertising-driven excitement over corporate products, but also because I was, and remain to this day, a nerd. I love trivia. I don’t necessarily mean that I seek out trivia-themed competition — though I’m always up for Trivial Pursuit, I was never in Quiz Bowl or did bar trivia night. No, I mean that I enjoy learning trivial information for its own sake. I read Wikipedia for fun. I tell “interesting anecdotes” about long-dead kings that have caused the occasional eye to glaze over.

Pretty much from the beginning, people told me “You should be on Jeopardy!” I believe I actually sent in a 3 x 5 card one year in an attempt to get into the teen tournament; I never heard back. As I grew into adulthood, I stopped watching the show on any sort of regular basis, but it was always in the back of my mind — if I were ever going to do any kind of game show, that would be the one. And this year, it actually happened. There seems to be some kind of rule that if you go on Jeopardy, you write about it on the Internet — I found plenty of narratives as I was preparing to be on the show — so here’s my contribution.

Getting on

As was the case for most things in this life that I’ve done that have been impressive, it was my wife Amber who convinced me to actually do something about it. A little research showed that the first stage of the tryouts is now online. You sign up to be contacted when the test is given, and you wait for what seems like an eternity, and then Sony Pictures (the show’s ultimate corporate parent) e-mails you a precise time when you need to log on to their site for the test. For me, this was in February of 2007. It consisted of 50 short trivia questions, which you have something like 15 seconds apiece to answer (and no, you don’t have to do it in the form of a question). I was pretty pleased at how that test went — I felt like I knew the bulk of the answers for certain and had reasonable guesses for most of the rest. You also tell them where you’d be willing to travel to to try out in person (I said Philly and DC) and then you wait some more.

Three months later, I was headed to the Mayflower Hotel in DC for the tryout. In the interim, of course, I had been scouring the Internets for information about what to expect, and what I should be doing to prepare. Apparently (so went the consensus) passing the trivia test essentially told them that you were smart enough (or at least trivia-addled enough) to make a good showing in that regard. What they wanted to see at the tryout was how telegenic you were. Do you speak up and make eye contact with your fellow human beings, or do you mumble into your shoulder? I am embarrassed to admit that on the train down to Washington, I was feeling kind of smug about my chances. I imagined that my competitors would all be borderline Aspergers cases, while I would wow them with my good looks and social graces.

In fact, everyone else in my tryout group — there were about twenty, and we were the third group of the day — was funny, personable, attractive, and, of course, terrifyingly smart. This obviously made me nervous, but it was still a fun event. Jeopardy’s team of contestant wranglers, led by Maggie and Robert, are really great — funny and nice and warm. And why wouldn’t they be? They have a great job. They put us through our paces, playing a fake game, doing a fake interview-with-Alex segment (“Tell us what you’d do with the money … not anything boring!”), and generally assessing our TV-worthiness. We also had to take another written trivia test (the logic being that you could have had all of your smart friends in the room with you when you took the online version), which I felt pretty much the same about as I did the online test. Then they staple your paperwork to a Polaroid of you and bid you good luck. I was in the pool for the next 18 months, and if I hadn’t heard from them in a year, I could sign up to take the online test again. Don’t call us, we’ll call you.

I headed back to the Baltimore not sure how to feel — I thought I had done well, but I didn’t feel like I was an incredible standout. I knew that they had hundreds of other potentials from around the country. I knew that one of the other people at my DC tryout was there for his second go-round. I hoped I’d get on, but at some level I didn’t think it would happen, and as the months went on, I resigned myself to signing up against next year.

Then, in March, I got The Call.

It’s really happening!

Maggie was very calm on the phone (which may have been the only time I heard her calm). “We just want to make sure this information we have is still correct,” she said, and I sort of half-thought they were just keeping their files up to date. But at the end, she very casually said, “So, we want you to come out to Los Angeles to film Jeopardy on April 22.”

This was barely a month away! Fortunately, my wife was able to take time off of work. We made arrangements to fly to LA (frequent flier miles, huzzah!) and decided to make a little mini-vacation out of it, staying with friends for all except the two nights just before filming, when we booked rooms in the hotel just up the street from the studio. I’m given to understand that back in the day, they paid for your travel and accommodations; now, it’s up to you to arrange all that, but, instead of a year’s supply of TurtleWax or a vacation to somewhere you don’t want to go, the third place winner gets $1,000 and the second place $2,000, which ought to cover your trip. (UPDATE: Since writing this, I’ve spoken to a couple of people who were on the show in the days before cash prizes for losers, and have learned that they never paid for you go out to LA. So huzzah for rule changes!)

Before I left, though, I did two very important things. I started watching the show every night, using a click pen as a buzzer substitute. And I hashed out Final Jeopardy betting strategies with my good friend and faithful reader Zipper the Mule. She’s both a gambler and math whiz, and she guided me through the rather confusing set of rules about how much you should bet if you really want to win, and printed up a cheat sheet for me. I was pretty sure I had it down.

Spending time in LA with Amber and our friends for a few days was actually kind of relaxing — it distracted me a little bit and stopped me from getting too worked up. I knew also that taking a mysterious vacation would arouse suspicions in my readers, so I took my laptop and blogged from the road, so none of you were the wiser! On Monday night, we checked into the Radisson in not-so-scenic Culver City; Tuesday morning, it was on.

What it’s like

OK, this is the part where I stop with all this personal reminiscing and get on with it and tell you what it’s like to be on the show already.

The packet I got from the Jeopardy staff said that I needed to bring three changes of clothes (nice clothes — they used the phrase “these are the sort of upscale looks we’re looking for”), and that I should be prepared to be at the studio both Tuesday and Wednesday. Contestants have to be at the studio at 8 am sharp, but your guests can’t arrive until 10:30, so they run a courtesy shuttle from the hotel. You might think that this would be a hotbed of mutual animosity, seeing as we would soon be going head-to-head for serious cash money, but in fact everyone was very cheerful and friendly, and, as you might imagine, we all had certain qualities in common.

Once we arrived and it was determined that none of us were trying to sneak a gun onto the set, we hung out in the green room for most of the morning, going through the legal paperwork, learning about how to do our dreadful “Hometown Howdy” (the promo you need to film for your local media market), and finding out about the various rules and quirks to the game. (For instance: in the first round, you’re allowed one instance of forgetting to respond in the form of the question, and in Final Jeopardy, you can misspell your answer as long as you do so phonetically.)

Then you’re led onto the set, which is an amazing experience in and of itself. My grandfather had seen the Price Is Right filmed once, and every time that show came on TV, he had to mention how small the set was in real life; I now understand why, because it does seem ludicrously cramped compared to how you imagine it. They take you on a little tour, introduce you to the golden voiced Johnny Gilbert, and then let you play a mock game, or part of one, against your opponents. This is when I finally encountered the thing I had been dreading all this time: the buzzer.

That damn buzzer

You know how sometimes you’re watching the show at home, and one of the contestants just never seems to ring in, and you think, “Gee, they’re not so smart, how’d they get on this show?” I will pretty much guarantee you that they’re having problems with the buzzer.

Buzzing in is not just a matter of being fast (which is just as well, as I wouldn’t have done well with that either). The clues are very easy to read from where you stand behind the podium, so you’re probably going to finish reading in your head it before Alex’s mellifluous voice gets even halfway through it. But you can’t just buzz in and interrupt him; that would be rude! And if you tried, nothing would happen. There’s a real live person sitting at the judge’s table, and he or she throws a switch that activates your buzzer once Alex is done talking. This also turns on a set of lights on either side of the board, which you can’t see at home; that’s your cue to buzz in, though some people on the Internet advise just listening for the last word in the clue instead. If you buzz in too early, you’re blocked out for a half-second or so, which is invariable enough time for someone to beat you to it. You’re supposed to pump the buzzer repeatedly rather than just pressing and holding it.

The whole thing just made me anxious. The practice game doesn’t last all that long — as they tell you in advance, they only leave you in long enough to get a hang of it, then give someone else a chance — and I thought I did OK, but not great. Then it was back to the green room (note: not actually green) for makeup and a last-minute pep talk, and then back to the set. It was nearly 11 and the filming was about to begin.

This … is … Jeopardy!

At no point during any of this, by the way, are you laughing it up with Alex Trebek. In fact, the man is nowhere to be seen. This is no doubt because they have to make sure that there’s no hint of partiality from him. In fact, other than the people who are specifically delegated for the care and feeding of contestants, they don’t want you having contact with anyone. If you have to leave the set to go to the bathroom, someone goes with you. Even though your guests are sitting only a few feet away from you, you’re not allowed to wave at them (a rule I broke when I saw my wife, and was gently admonished over).

Anyway, all the contestants arrived on the set, and two names (neither of them mine) were drawn at random to face the returning challenger, who had been keeping a low profile. (Because she had filmed her earlier show some weeks before, her return trip was paid for.) Alex only emerged onto the set — from a hidden door behind part of the big board, which no doubt leads back to his Fortress of Alextude — as the famous opening theme music played. Then the action started. Remember, the show is only half an hour long. It goes fast. They try to film more or less in real time, though if there are disputes or goofups, they can stop tape, or re-record audio during the commercial breaks. (I only saw the latter happen twice — once when Alex mispronounced a word, and once when a clue actually had the wrong year in it.)

In keeping with the attempt to keep things quick and in real time, the breaks in filming between rounds are actually as long as the real commercial breaks when the show is broadcast — the show is sent to local stations with these blank spots where ads can just be dropped in. During these breaks, Alex takes Q&A from the audience, and it’s from these moments that I can get as close as I can to answering the question that everyone asks me, which is “What is Alex Trebek really like?” As far as I can tell, he’s really nice. His kind of pompous on-air personality (which I don’t find as off-putting as some apparently do) drops away immediately; he’s funny, does random little accents for no reason, and most of his jokes are self-deprecating (and often involve his love of booze). But as for his actual interaction with the contestants, that’s limited entirely to what you see on screen during the broadcast of the actual show — again, no doubt to keep any worries about collusion at bay.

So after half an hour, the show is done filming. What comes next? Another show! They film five shows — an entire week’s worth — in one day of filming. There are about ten minutes between shows, during which, if you’re the champ, you run back to the green room and change clothes. (As the contestant wranglers say, “If Alex can do it, so can you.”) At the end of each show, they drew two more names — and each time my name wasn’t called. I sat through a whole week’s worth of shows in one afternoon and was one of only two people not called — they have extras, in case someone fails to show up or everyone ends the game with negative money or something, I guess. I would be coming back the next morning.

So the whole thing repeated on Wednesday, with a new batch of contestants. I actually wasn’t that broken up about it — I felt like sitting through the previous day had been good for acclimating me to the situation, and a good friend of mine was in town for a conference and would be able to keep Amber company at the studio on Wednesday. We went through the whole routine again (and I got another practice round with the buzzer), and I was told that I’d definitely be on one of the shows filmed that day, which was actually the last filming day of the season. (Jeopardy only films on Tuesday and Wednesdays; most of the technical people also work on Wheel of Fortune, which films on the adjacent set on Thursdays and Fridays.)

In the five shows I had seen filmed the previous day, there had been no repeat champions — everyone who won one game lost the next. The winner of the final show, the one that broadcast Friday, July 18, was a guy names Mark Wales. He was really nice and personable, and we had chatted for bit on the bus coming over that morning — he lived in Buffalo, my home town. As soon as his first game started, it was obvious that he was really good at the buzzer. He jumped out to an early lead, then hit the first Daily Double, bet it all — and got it wrong. Then he got a couple of other answers wrong, and was at -$1,000 by the first commercial break, and I remember thinking to myself, “That’s it, he’s done.” He wasn’t. He ended up storming back to win the game pretty handily.

For the first show filmed the next day, my name once again wasn’t called. That game turned out to be an epic struggle, with a groovy hippie grad student named Dan almost beating Mark, but getting the Final Jeopardy question wrong. It was clear at that point that Mark was really good — smart, good with the buzzer, and cool under pressure. Naturally, I was tapped to face him next.

This is really happening

The game itself is still something of a blur to me — when I watched it later, I was surprised at how little of it I actually remembered. But what I definitely remember was how hard it was for me to buzz in. It took what was probably only three or four minutes, but what felt like me to be an eternity, to get my first chance to answer a question, and that threw me. Once I got started, though, I did OK. I answered several high-value clues in the first round and ended up in second place at the end of it — closer to Joanne, our third opponent, than to Mark, but still in second.

In the middle of the first round comes that awkward moment when you have to make small talk with Alex. The chat is very structured — you have to submit a set of interesting anecdotes before hand, and you can pick one that you’d like most to talk about, though Alex might pick a different one. (He has them on index cards for reference.) I picked the blog, naturally, and though I wasn’t allowed to actually say the name on the air, I hope it served as a suitable shout out. I also wasn’t really able to convey this site’s somewhat jaundiced view of the comics; there are no doubt about 20 million people out there who think that I love (in fact, I think the phrasing I used was “LOOOoooove”) Rex Morgan, M.D., with a total absence of irony.

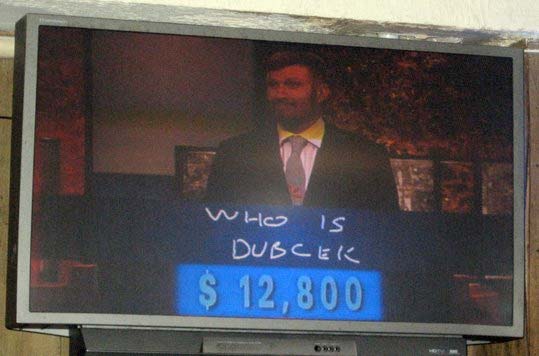

Anyway, the second round was more of the same: I did better than Joanne, but not as well as Mark, and Mark slowly pulled away from me, helped by the fact that he found (and got right) all three Daily Doubles. At the end of the Double Jeopardy round, I gave my first wrong answer, in the “State Fish” category: I said “swordfish” when I should have said “sailfish.” Yes, I do know the difference, and I swear the thing I was visualizing in my head was a sailfish, but there it was. This had me frantically checking my score (which you can see, by the way, above and to the left of the game board). I was worried that by losing that $2,000, my score had dipped to below half of Mark’s — which would have meant that I would be unable to catch him unless he bet very stupidly in Final Jeopardy, something he had shown no inclination to do to that point. Fortunately, the round ended with me at $12,800 and him at $25,200. If I got the Final Jeopardy clue right and he got it wrong, I would still win.

I haven’t actually said anything about what my emotional state was like while all this was going on. While I was in the thick of the game, I actually felt pretty calm. I was kind of irritated because I couldn’t buzz in as often as I liked, but I wasn’t having any of those dreaded mental blocks on clues were you know that at some level you know the answer but can’t summon it. Most of the clues I knew the answers to (whether I could buzz in and answer them was a different story), a few I was unsure of and didn’t buzz in. But during the commercial breaks, I became very aware of how much adrenaline was pumping through me, and how nervous I actually was.

It comes down to this

This all came crashing down on me when it came time to bet on Final Jeopardy. You get to see the category before you bet, and they give you scratch paper to do your math. The category was “World Leaders” — right up my alley! I love politics, I love international politics, I even wrote a damn satirical column about world leaders for Wonkette! And yet when it came time to do my betting, I realized that my brain — or at least those parts not dedicated to trivia — was completely fried. All the math and strategy I had studied with Zipper the Mule was gone. The situation wasn’t difficult to parse: Mark had almost twice as much as me, so I had to bet almost everything to have a chance of winning, which I did — all but $1 (because you can’t win with $0, so you might as well hedge against something totally wacky happening). I wrote down my bet, and then pressed the little button that registers it, after which there is no going back.

And this is the terrible part. Sometimes, when I leave the house and walk away, I am suddenly convinced that I have failed to lock the door behind me and have to go back and check. Or sometimes I think I have locked the door, but have forgotten to bring my key, and have to reach into my pocket check that. It’s not rational, but it’s something I experience often. And it was a similar sort of feeling I got when I hit that button — I suddenly became convinced that betting all but $1 was the wrong thing to do, that it would leave me a dollar short even if I got the clue right and Mark got it wrong, that I had screwed up and done something incredibly stupid and there was no way to fix it. It totally deflated me. Then, some other random part of my brain convinced me that by leaving off that dollar, Mark and I would end up tied if I got the final clue right and he was wrong, and we would go on to the next game together. This perked me up a bit, though the thought of competing against him again was pretty worrisome.

As anyone who can do basic arithmetic knows, both of these assumptions were completely off-base. Mark would obviously bet at least $400 to guarantee that he would win if we were both right. If he did that, and I was right and he was wrong, I would end up with $25,599 and he would end up with $24,800, and I would win outright. But this comforting math was beyond my capabilities at the time. I was rattled, and I’d like to think anyway that this affected what came next. When the clue was finally revealed, this was it:

Born in Kiev & later a U.S. citizen, this leader became Prime Minister in 1969 of a country founded in the 20th century.

This is in many ways a typical Jeopardy clue, in that it’s packed with information — there are at least four different data points in it from which to construct your guess. And I drew a blank. I saw “Kiev” and “country founded in the 20th century” and my mind immediately went to the ex-USSR. Then I saw “1969” and knew that that couldn’t be right, but my mind stubbornly refused to leave Eastern Europe. What Eastern European countries were founded in the 20th century and existed in 1969? Poland, but I couldn’t think of any Polish prime ministers; Yugoslavia would have also fit the bill, but it didn’t occur to me at the time. What about Czechoslovakia? 1969 … Prague Spring … maybe Alexander Dubcek, the reformist Communist leader who was ousted by the Soviet invasion and replaced by people more loyal to Moscow? As that famous music, which I was hearing for the seventh time in two days, was hitting its last note, I scrawled his name out as fast as I could.

I should say that, even as I went through this chain of circumstantial logic, I knew — knew with absolute certainty — that I was wrong. And in fact later research revealed that Alexander Dubcek met virtually none of the requirements of the clue. He had never been a U.S. citizen (though he was conceived in the United States); he wasn’t born in Kiev; he wasn’t Prime Minister (his title was “First Secretary of the Communist Party”); and he came to power in 1968, not 1969. But at least I wrote down something. And it actually brought up one of my favorite moments of the show. I’ve heard a lot of people make fun of Alex Trebek, saying that he acts so superior but is just reading all the answers off of a cue card, so how smart can he be? As you can see above, I only had time to write the man’s last name; when Alex saw it, he murmured “Ah, Alexander Dubcek.” He knew who I was talking about! And this was someone so far off base that there was no reason to encounter his name when researching this particular clue. For some reason that really tickled me, even as he informed me regretfully that I was wrong and my total dropped down to $1.

I ended up in third place. Joanne hadn’t gotten the answer either, but had bet small (smart, in her position). Mark, as he had been doing all week, got it right: the answer was Golda Meir. Golda Meir! The Jewish guy, the one obsessed with history and politics, had missed Golda Meir! Oy vey!

Aftermath

For much of the rest of the afternoon, I was pretty bummed, which was exacerbated by the fact that I was experiencing an adrenaline crash. But by the end of they day, I was feeling better about it. This was helped by the fact that Mark had gotten the Final Jeopardy question right, which meant that even if I had been able to summon up Golda’s name, he would have still won. And the experience overall had been really great. This was something I had been dreaming about for most of my life, and I had really done it! I got to talk about Rex Morgan on TV! Alex had said something nice about my tie! And hell, because we flew out on frequent flier miles, once I got that $1,000 check I’d still come out ahead a bit financially, even after the hotel and the rental car and the posh dinners in which I drowned my sorrows.

The hardest part of the next three months was having to keep the results secret. We did tell a select few — our parents, Amber’s brother, some close friends — but everyone wanted to know, and we kept our mouths shut. (The Jeopardy folks ask that you try to keep things secret for the most part, because if word gets too far around it spoils the fun.) Amusingly, there were a couple of things we did that convinced people that I had actually hit it big. We left for a two-week vacation in Italy (which we had been saving up for for two years); and we bought a new car (which we had to buy because our 14-year-old Toyota had finally bit the dust, and which we paid for in classic American fashion by financing it).

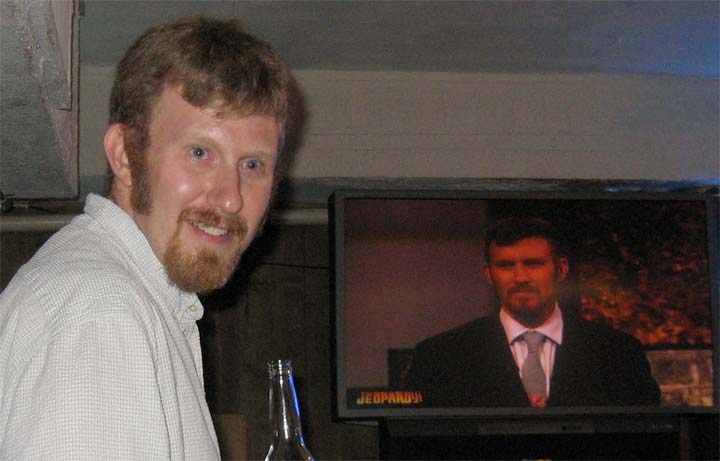

Right away it became clear that a lot of people wanted to watch the show with us, to the point that we knew we wouldn’t be able to have a party at our house. We talked to the folks at a bar up the street, which had tons of TVs typically tuned to ESPN; turns out they were Jeopardy fanatics and more than happy to have a big crowd on a Tuesday night. As the days ticked down to the actual show, I got nervous all over again. Did I really want to see myself on TV surrounded by people I knew? What if I had some horrible facial or vocal tic that everyone else knew about but I didn’t? What if they were disappointed?

In the end, about fifty people I knew showed up — family, friends, and even faithful readers wolfdog and yellojkt, the latter of whom wrote about the experience on his own blog — and there were probably another fifteen or so who just happened to be there. It was a blast. Everyone cheered when I got things right and booed my opponents. One of my wife’s coworkers even ran a pool on how much I won (another coworker, borrowing a strategy from the Price is Right, bet on $1 and went home with $55). Even when I lost, they all cheered. I felt like a hero.

As of this writing, Mark is still the champ, having won five days and counting — I wish him luck, because if you’re going to be beaten, you should lose to the best. If you ever feel like trying out for a game show, I heartily recommend it — it’s a blast! Especially Jeopardy, because everyone — everyone! — involved is just really nice and warm and funny and smart.

Oh, and I was told that I couldn’t try out for Jeopardy again — for as long as Alex hosts the show. On the day my show was broadcast, he turned 68. Maybe it’s time to think about retiring, isn’t it, Trebek? Who knows, maybe I’ll be back.