Literary Sunday

Post Content

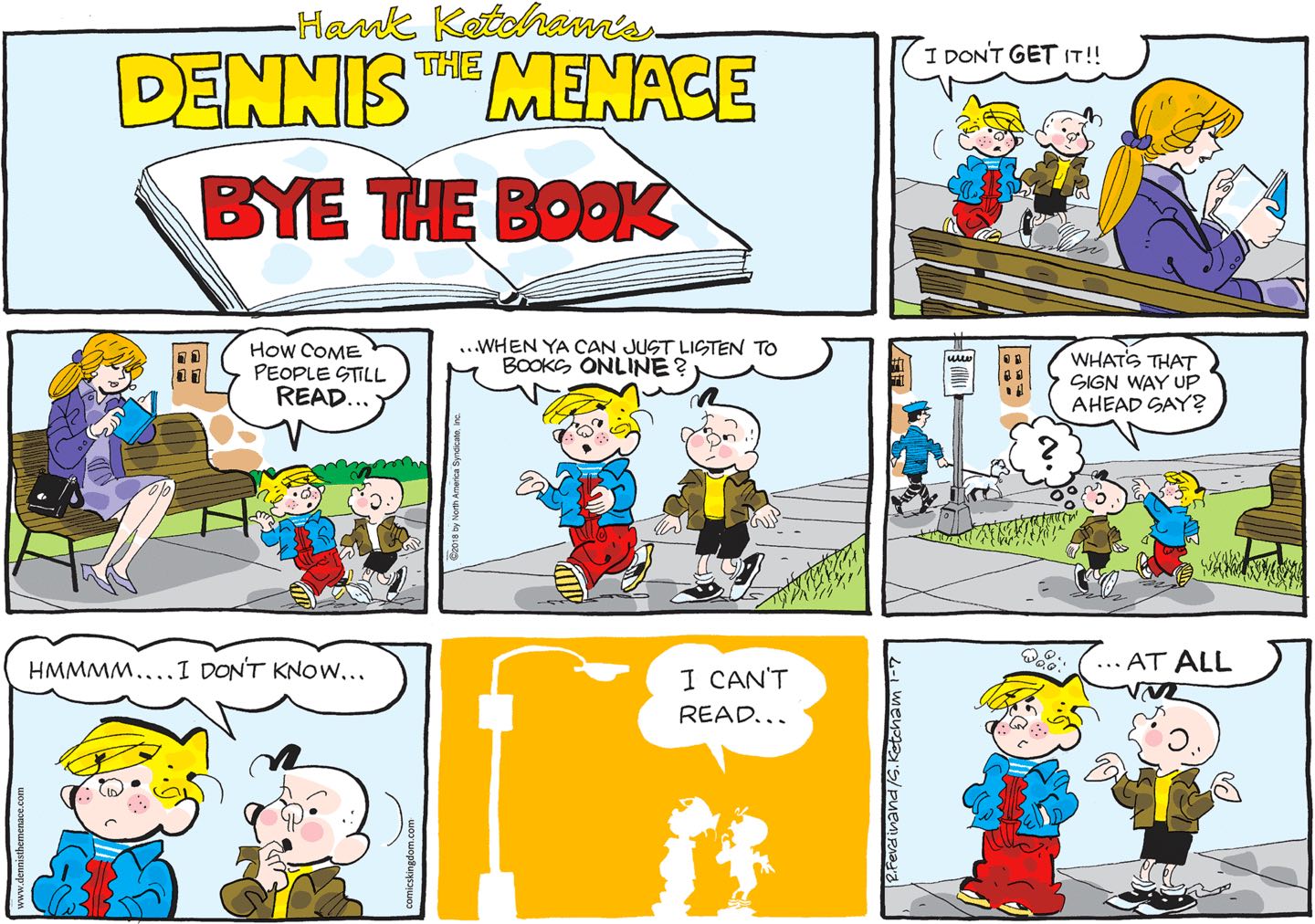

Dennis the Menace, 1/7/18

One of the anecdotes my wife and I repeat to each other endlessly comes from years ago, when we were driving through Pennsylvania and stopped, as was our habit, at Clyde Peeling’s Reptile Land, where we never paid to actually see the animals but took advantage of the Subway, bathrooms, and gift shop anyway. On this trip there was this very sullen-looking little boy, maybe seven or eight years old, wandering through the store, and then his mother came up to him, and said to him, with a voice that was trembling and almost fearful, “Look, it’s a book about dinosaurs! You love dinosaurs!” He squinted at her, and then, with a voice loaded with contempt, said, “I don’t read,” and then walked away, leaving her standing there with the book.

This is, of course, a horror story about our society’s coming decline into idiocracy, but I’d like to imagine that maybe there was some comeuppance in store for the kid, like the one Dennis is experiencing here. Maybe there’ll be a horrified realization, once it’s too late, that a generation that refuses to read will be followed by a generation that couldn’t read even if it wanted to.

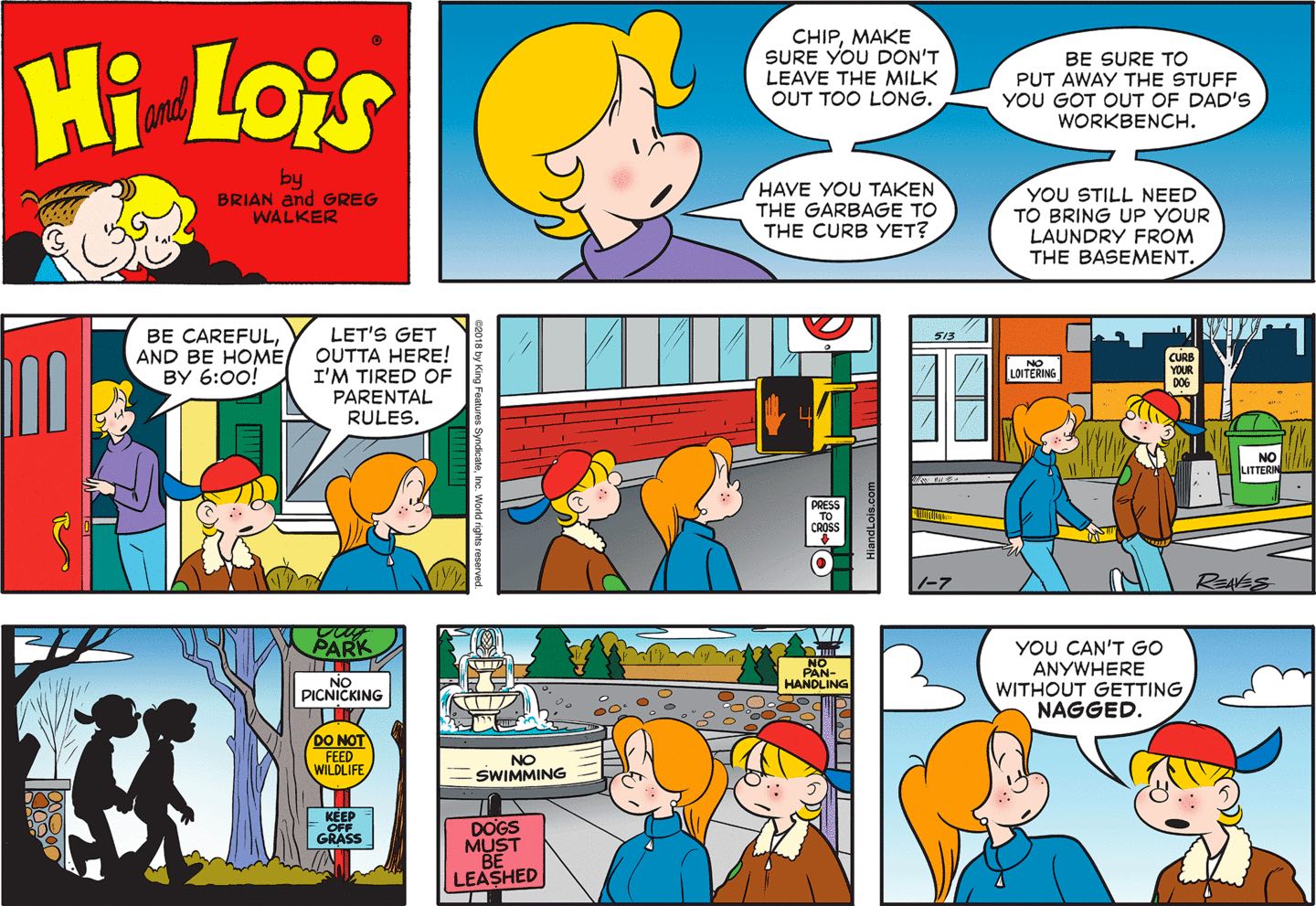

Hi and Lois, 1/7/18

Here’s another story for you about illiteracy that I love, although I’m not personally involved in this one because most of it took place decades or millennia ago. Once upon a time, there were a bunch of clay tablets dug up in Greece with an alphabet on them nobody could read. Archaeologists called the script Linear B (because it was clearly related to Linear A, another alphabet nobody could read), and various dating techniques pegged those tablets as being from between 1400 and 1250 BC. The first written material in Greek doesn’t appear until the 770s BC, and the Greeks themselves had legends of other people who lived in Greece before them, so the assumption was that Linear B was those people’s vanished language. And what’s more romantic than a vanished language? Think of all the mysterious culture locked in those tablets — the poetry, the histories, the odes to forgotten gods — tantalizingly right in front of us, and yet indecipherable.

In the 1950s, though, some British classicists figured out that Linear B (though not Linear A, which is still undeciphered) was in fact Greek after all, an earlier form of the Greek language written using a clumsily adapted syllabary system that was unrelated to the Greek alphabet that emerged centuries later. And what, after this breakthrough, did those tablets turn out to be telling us? There were no poems or tales of dead heroes at all. The tablets consisted entirely of administrative records for the palaces where they were found, keeping track of how much grain, wool, sheep, and wine had been extracted from the peasantry and handed over to the army and the temples. Some royal accountants had apparently got wind from some other culture of the idea that you could record words by making marks in clay and realized that would make their jobs loads easier, but they hadn’t bothered to sell anyone else on the concept. Or maybe they tried but nobody — not the priests, not the poets, not the kings — saw the point in it.

And in the middle of the 1200s, this whole early Greek civilization went up in flames — literally, all the palaces were burned down in a relatively short timeframe. The fires hardened the clay tablets stored in the palace basements, which is why we have so many of them; after the culture collapsed, nobody wrote anything in Linear B anymore, because there were no more kings to take stuff from the peasants and give it to the soldiers and priests.

To us, a societal loss of literacy is a terrifying thought. But to those ancient Greek farmers, none of whom had been able to read in the first place, it must have been liberating. Maybe Chip and his girlfriend are seeing the possible anarchic paradise that Joey has to look forward to. Everywhere they go, writing is the means by which an omnipresent state imposes its will on everyday behavior. But Joey? Joey can do whatever he wants. He doesn’t know any better, and that’s the purest freedom of all.